DR KELLY PARSONS

Post-doctoral Researcher: Food Policy

kelly@kellyparsons.co.uk

DR KELLY PARSONS

Post-doctoral Researcher: Food Policy

kelly@kellyparsons.co.uk

An Overview of Food Systems,

and the role of Policy

What are food systems and why are they important?

The term “food system” has been around for several decades, but has become a mainstream term in both academic and non-academic language in recent years.

The context for coalescing around this term is recognition that some of the world’s most challenging problems - from obesity, to climate change - are associated with food, and how food-related activities and outcomes are linked to one another. This has led to the conceptualisation of food as a ‘system’ – an ‘interconnected system of everything and everybody that influences, and is influenced by, the activities involved in bringing food from farm to fork and beyond’ (Parsons, Hawkes and Wells 2019).

Conceptualising food as a system in this way helps to highlight how activities in one part of that system can have impacts elsewhere, for example how what food is produced impacts on people’s diets, or how protecting biodiversity in forests can limit people’s livelihoods if land for growing food is protected. You can read more about what the food system is, and see a visual representation of it created by myself and colleagues in the brief written by Parsons, Hawkes and Wells (2019) under Food Systems.

Source: Parsons, Hawkes and Wells 2019

What is the role of policy in food systems?

Policy is one of the activities that influence food systems. It is also one of the key 'levers' (along with knowledge, technology, and others) to change or 'transform' the system. You can read more about food systems policy levers under the tab Food Policy Levers.

Many policy interventions targeting that system focus on a single activity (e.g. eating/consumption) and single outcome (e.g. nutrition), but because of the connected nature of the system each of these interventions has potential to create cascading effects into other segments and outcomes, leading to unintended consequences and incoherence between competing objectives. An established example is how policies to encourage increased productivity in particular types of farming can damage the environment. Another is how trade policy impacts nutrition, for example by making certain types of food more available (this can be healthy food such as fruit and vegetables, or unhealthy highly processed foods). Though evidence is slowly building, we still don't have a detailed understanding of the system interactions between different objectives and activities related to food.

The concept of policy coherence is a way of articulating the need to identify and address conflicts between different objectives and activities, and to find opportunities for policies to reinforce one another, to make sure they are as effective as possible (illustrated in the diagram below). You can read about policy coherence - why it is important, the different types of incoherence that may cause problems and how it can be analysed - in the brief written by Parsons and Hawkes (2019), under Policy Coherence.

Source: Parsons and Hawkes 2019

Source: Parsons and Hawkes 2019

Who makes food policy?

One of the main reasons why policies addressing the food system can result in incoherence is that they are made by many different organisations. Historically governments have tended to address food issues through policies, strategies or plans focusing on one or occasionally two aspects concerning food independently, because their primary concern was ensuring an adequate food supply through agriculture and trade. The term food policy was (and still is in some countries) associated with food supply policies. Changes in how food is produced and consumed, and the resulting impacts on the health of the planet and its people, means food has become relevant for policy areas including health, environment, planning, education and migration, though it is rarely a top priority. The term food policy has morphed to being used as an umbrella term for the many policies related to food (it is also used to refer to a particular framework policy on food - for example a country government's 'national food policy').

Policies addressing the food system are made by different government ministries - for example policies about what food is grown and how, by agriculture ministries, or policies about what food can be advertised, by health ministries. They can be made at different levels of government, such as national-level, or local level, and are also not limited to the government, or 'public sector'. Food policy also involves activities in the private sector, for example when businesses set up their own certification or labelling schemes, and in the 'third sector' (or food civil society) which, for example, runs most of the food banks which exist to provide direct food assistance to those in need. This spread can lead to disconnects between the various activities.

Source: Parsons 2019

For several decades this fragmentation - and particularly that between different policy sectors like agriculture and health - has led to calls for more connected policies related to food.

To make connections you first need to understand who it is that might need to be connected. A mapping exercise of the different ministries in England, and their potential role in influencing the food system, identified more than 16 departments, plus other governmental bodies. Understanding where the responsibilities for different bits of the food system lie, is also important if you want to change the system.

Similar mapping, highlighting a similar number of relevant ministries, has since been done in India and South Africa.

This kind of mapping can also be used to create an 'inventory' of a country or city's policies relevant to food systems. The accompanying report to the map on England shown below has a chapter on each key department, detailing the current 'live' policies in that particular policy area.

You can read more about the mapping, and the method behind it, under the Who Makes Food Policy tab.

Source: Parsons 2020

This type of mapping helps to establish the way food policymaking is organised - or 'food governance' arrangements. You can read a brief about how food governance is organised at the global level (Parsons and Hawkes 2019) and how this impacts on the ability to address food systems holistically, and about the way governance arrangements at local, city, level can impact on food policymaking opportunities (Parsons, Lang and Barling 2021), under the Food Governance tab.

How connected are food systems issues in the current policy approach?

Knowing who is responsible for what is only part of the story. Once you have an idea who is involved in making food-related policy, you can then begin to map out how food systems issues which cut across multiple policy sectors, or the remits of multiple ministries - for example obesity, or food-related climate impacts - are, or are not, being connected. This can help to identify where better connections could improve policy intervention to improve food systems, and facilitate a 'food systems approach' to policy. For an example of this kind of screening for connections, see Food Policy Connections.

Source: Parsons 2021

How can food systems policies be made in a more connected way?

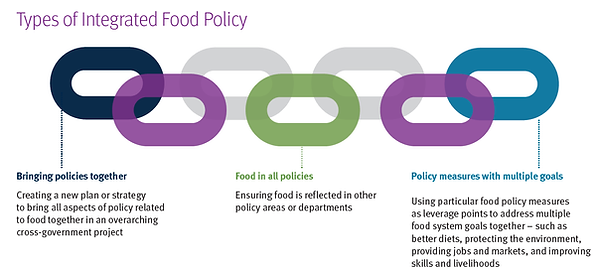

A food systems approach to food-related policies means making connections across policy areas, levels of government, and between the public, private and third sectors. One way that can be done is 'integrated food policy'. There are different types of integrated food policy. One type is where a government attempts to create a cross-cutting framework policy on food, like a national or city food policy, plan or strategy. Another is an approach used in some cities, which involves embedding food in other policy sectors - such as planning, or transport. Currently there are few examples of integrated food policy, and those that have been tried have often fallen short of their aims. These are discussed in the briefs listed under Integrated Food Policy.

Source: Parsons 2019

Food Governance Mechanisms

Creating an integrated food policy - like a national food strategy - is one 'mechanism' for joining up. There are many other ways, including establishing a cross-government taskforce or committee, creating a dedicated body (which can be inside government or arms-length), or a dedicated minister or ministry.

I have developed a typology of different mechanisms or 'tools for connecting food policy', which you can see under the Food Governance tab.

Some of these mechanisms have been tried, for example England's now defunct Cabinet Sub-Committee on Food, or the Scottish Food Commission independent advisory body. Others - like an 'IPCC for food' type of global level structure have been proposed but not implemented.

The covid-19 pandemic amplified calls for new structures and processes to support more effective, connected working on food, and get food system challenges up the policy agenda. In the USA, a new intergovernmental task force has been proposed to ‘orchestrate more effective collaboration between the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, the Food and Drug Administration and the agencies that oversee and enforce worker safety: the Centers for Disease Control and the Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration’. Other suggestions include a White House-appointed food security czar, and a new Department of Food Security, to coordinate action among the various actors in the food-supply chain.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the government has been urged to appoint a new minister for hunger in response to food insecurity issues which have been magnified by Covid-19. And health campaign groups Action on Salt and Action on Sugar have called for a ‘new independent and transparent food watchdog, free from ministerial, industry and other vested-interest influences’, focused on providing dietary information to the public, to address the connection between obesity and Covid-19.

You can read some of the proposals which have been made, and my thoughts on this subject, in a blog post here.

The evidence base on the most effective arrangements is poor and more attention is needed on how different governments make food policy, and how they coordinate their activities. Interest from policymakers on how to connect their food-related policies is growing, but our knowledge lags behind.

You can find more details of my research in the 'Research Themes' pages.